Meaning of Red Circle and Gold Circle Japanese Buddhist Art

Lotus motif from Sanchi complex

An "Indra Postal service" at Sanchi

Buddhist symbolism is the use of symbols (Sanskrit: pratīka) to represent certain aspects of the Buddha's Dharma (teaching). Early Buddhist symbols which remain important today include the Dharma wheel, the Indian lotus, the three jewels and the Bodhi tree.[1]

Anthropomorphic symbolism depicting the Buddha (as well as other figures) became very popular around the get-go century CE with the arts of Mathura and the Greco-Buddhist fine art of Gandhara. New symbols continued to develop into the medieval menstruum, with Vajrayana Buddhism adopting further symbols such as the stylized double vajra. In the modern era, new symbols like the Buddhist flag were also adopted.

Many symbols are depicted in early Buddhist fine art. Many of these are aboriginal, pre-Buddhist and pan-Indian symbols of auspiciousness (mangala).[two] According to Karlsson, Buddhists adopted these signs because "they were meaningful, important and well-known to the majority of the people in India." They also may have had apotropaic uses, and thus they "must have been a way for Buddhists to protect themselves, but as well a fashion of popularizing and strengthening the Buddhist movement."[3]

At its founding in 1952, the Globe Fellowship of Buddhists adopted two symbols to represent Buddhism.[4] These were a traditional viii-spoked Dharma wheel and the v-colored flag.

Early on Buddhist symbols [edit]

The earliest Buddhist art is from the Mauryan era (322 BCE – 184 BCE), at that place is picayune archeological evidence for pre-Mauryan catamenia symbolism.[v] Early Buddhist art (circa 2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE) is commonly (but non exclusively) aniconic (i.eastward. lacking an anthropomorphic image), and instead used various symbols to depict the Buddha. The all-time examples of this aniconic period symbolism tin can be found at sites like Sanchi, Amaravati, Bharhut, Bodhgaya and Sarnath.[half dozen] According to Karlsson, three specific signs, the Bodhi tree, the Dharma wheel, and the stupa, occur frequently at all these major sites and thus "the earliest Buddhist cult exercise focused on these three objects".[7]

Amongst the earliest and most common Buddhist symbols establish in these early Buddhist sites are the stupa (and the relics therein), the Dharma cycle, the Bodhi Tree, the triratna (three jewels), the vajra seat, the lotus bloom, and the Buddha footprint.[8] [ane] [9] [half-dozen] Several animals are also widely depicted, such every bit elephants, lions, nāga and deer.[8] Contemporary Buddhist fine art contains numerous symbols, including unique symbols non establish in early Buddhism.

Gallery [edit]

-

A Dharmachakra being revered

-

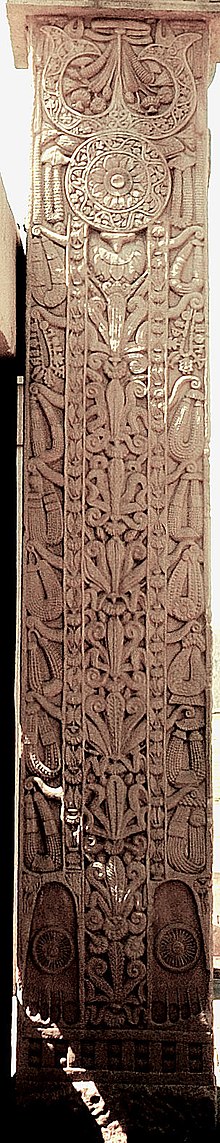

Pinnacles from Bharhut depicting Dharmawheels and Lotus roundels

-

Illustrations from Sanchi, depicting a dharma chakra, devotees, and deer

-

Dharmachakra, and elephants

-

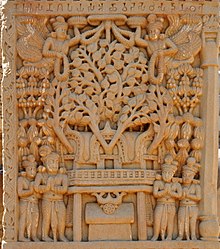

Bodhi tree showing distinctive heart-shaped leaves and devas

-

Relief of the Diamond Throne (Vajrasana) with two triratnas

-

Buddhapada busy with lotus roundels, Triratna's and swastikas, 2nd century, Gandhara

-

Buddhapada with other symbols

-

Carved decorations on the doorway of Sanchi stupa, notation the dharma chakra, diverse animals, and Triratna (with srivasta in the center).

-

Empty throne and bodhi tree

-

Bodhi tree with garlands, an umbrella, and Triratna's

-

The Buddha turning the dharma bicycle at deer park

-

The Buddha's horse, Kanthaka, and an attendant with a chakra (royal umbrella)

-

Depiction of the dream of Maya (Buddha'due south mother), in which the Buddha enters her side as a white elephant, from Bharhut

-

A Pillar depicting an empty throne, the Naga rex Mucalinda and the Bodhi tree

-

A Naga at Sanchi

-

A delineation of devas holding up the begging bowl of Buddha.

Southeast Asian Buddhist symbols [edit]

Theravada Buddhist art is strongly influenced by the Indian Buddhist art styles like the Amaravati and Gupta styles.[10] Thus, Theravada Buddhism retained most of the classic Indian Buddhist symbols such as the Dharma wheel, though in many cases, these symbols became more elaborately busy with gold, jewels and other designs.

Unlike artistic styles also adult throughout the Theravada globe as well as unique ways of depicting the Buddha (such as the Thai style and the Khmer mode) containing their own means of using Buddhist symbols.

Gallery [edit]

-

Dhamma cycle and deer from Dvaravati

-

Dhamma wheel, Dvaravati period, Khao Klang Nai, Si Thep Historical Park, Thailand

-

A Thai Dhamma wheel at Wat Phothivihan, Tumpat, Kelantan

-

Dhamma wheel at Wat Maisuwankiri, Tumpat, Malaysia

-

Dhamma bicycle at

-

A mold and a Bai Sema rock (monastery boundary rock)

-

-

Dhammacakka on Main Gable, Wat Phra Putthabat Tak Pha, Lamphun

-

A Thai style Dhamma bike

-

Buddha Left Footprint, Wat Phra That Doi Suthep, Chiang Mai

-

Burmese Pali manuscript depicting a hamsa bird.

-

Panthera leo in a Burmese Pali Manuscript

East Asian Buddhist symbols [edit]

Statue of Guanyin with diverse attributes (cintamani, chakra, lotus, prayer beads)

East Asian Buddhism adopted many of the classic Buddhist symbolism outlined higher up. During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) Buddhist symbolism became widespread, and symbols similar the swastika and the Dharma wheel (Chinese: 法輪; pinyin: fălún, "bicycle of life") became well known in China. There were also more elaborate symbols, similar Buddhist mandalas and complex images of Buddhas and bodhisattva figures.[xi]

At that place are also some symbols that are by and large unique to Eastward Asian Buddhism, including the purple robe(which indicated a particularly eminent monastic), the ruyi scepter, the "wooden fish", the ring staff (khakkhara), The Eighteen Arhats (or Luohan) (Chinese: 十八羅漢)the "ever burning lamp" (changmingdeng) and diverse kinds of Buddhist amulets or charms, such equally Japanese omamori and ofuda, and Chinese fu (符) or fulu.[12] [xiii] [14]

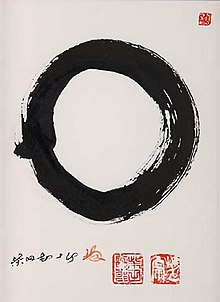

Chinese Buddhism too adopted traditional pre-Buddhist Chinese symbols and deities, including coin trees, Chinese dragons, and Chinese gods like the Jade emperor and various generals similar Guan Yu.[15] [xvi] Japanese Buddhism besides adult some unique symbols of its own. For example, in Japanese Zen, a widely used symbol is the ensō, a hand-drawn black circumvolve.[17]

Gallery [edit]

-

Chinese Buddhist priest's silk robe with various Buddhist symbols

-

A statue of bodhisattva Kṣitigarbha holding a cintamani rock and a ring staff

-

The Flaming Sword of Wisdom

-

Bhutanese throne comprehend with a gankyil

-

Sometime flag of Sikkim with Dharma wheel and gankyil

-

Chinese depiction of Manjushri, riding a lion and holding a ruyi scepter

-

A japanese painting of Manjushri (monju) holding a sword and a lotus topped with a sutra, Kamakura period

-

-

Bodhidharma is widely depicted in Zen, the moon symbolizes enlightenment

-

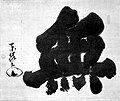

Calligraphy of the kanji for Mu (無, "no", "non") widely used in Zen calligraphy

-

Bronze finial of a monk's band staff (shakujō), Japan

-

A portrait of Zen monk Ingen property a wooden staff and a fly-whisk

Vajrayana Buddhist symbols [edit]

Five esoteric ritual objects from Japan including vajras, knife and bong.

A viśvavajra or "double vajra" appears in the emblem of Bhutan

Mantric Buddhism (Guhyamantra, "Secret Mantra") or Vajrayana has numerous esoteric symbols which are not common in other forms of Buddhism.

The vajra is a key symbol in Vajrayana Buddhism. It represents indestructibility (like a diamond), emptiness as well as power (like a thunder bolt, which was the weapon of the Vedic god Indra). According to Beer, information technology represents "the impenetrable, imperishable, immovable, immutable, indivisible, and indestructible land of absolute reality, which is the enlightenment of Buddhahood."[18] The vajra is often paired with a bell (vajra-ghanta), which represents the feminine principle of wisdom. When paired together, they correspond the perfect union of wisdom or emptiness (bell) and method or proficient means (vajra).[19] At that place is also what is called the "crossed vajra" (vishva-vajra), which has four vajra heads emanating from a central hub.[20]

Other tantric ritual symbols include the ritual knife (kila), tantric staff (khatvanga), the skull loving cup (kapala), the flaying pocketknife (kartika), manus pulsate (damaru) and the thigh bone trumpet (kangling).[21]

Other Vajrayana symbols popular in Tibetan Buddhism include the bhavacakra (bike of life), mandalas, the number 108 and the Buddha eyes (or wisdom eyes) unremarkably seen on Nepalese stupas such as at Boudhanath.

There are various mythical creatures used in Vajrayana fine art as well: Snowfall Panthera leo, Wind Horse, dragon, garuda and tiger. The pop mantra "om mani padme hum" is widely used to symbolize compassion and is ordinarily seen inscribed on rocks, prayer wheels, stupas and art. In Dzogchen, the mirror is ane important symbol of rigpa.

Tibetan Buddhist architecture [edit]

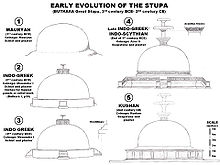

Viii types of Tibetan stupas

Tibetan Buddhist architecture is centered on the stupa, called in Tibetan Wylie: mchod rten, THL: chörten. The chörten consists of five parts that represent the mahābhūta (5 elements). The base is foursquare which represents the earth chemical element, above that sits a dome representing water, on that is a cone representing fire, on the tip of the cone is a crescent representing air, inside the crescent is a flame representing ether. The tapering of the flame to a point can also be said to represent consciousness as a sixth element. The chörten presents these elements of the torso in the order of the process of dissolution at death.[22]

Tibetan temples are often three-storied. The three tin can represent many aspects such every bit the Trikaya (iii aspects) of a Buddha. The ground story may have a statue of the historical Buddha Gautama and depictions of Earth and and so represent the nirmāṇakāya. The first story may accept Buddha and elaborate ornamentation representing rising above the homo condition and the sambhogakāya. The second story may have a primordial Adi-Buddha in Yab-Yum (sexual spousal relationship with his female counterpart) and be otherwise unadorned representing a return to the absolute reality and the dharmakāya "truth trunk".[22]

Colour in Tibetan Buddhism [edit]

In Tibetan Buddhist fine art, diverse colors and elements are associated with the 5 Buddha families and other aspects and symbols:[22] [23] [24]

| Colour | Symbolises | Buddha | Direction | Element | Transforming effect | Syllable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Purity, primordial being | Vairocana | East (or, in alternate organization, North) | Water | Ignorance → Awareness of reality | Om |

| Green | Peace, protection from harm | Amoghasiddhi | North (or n/a) | Sky | jealousy → Accomplishing pristine awareness | Ma |

| Xanthous | Wealth, beauty | Ratnasaṃbhava | South (or Due west) | Earth | Pride → Awareness of sameness | Ni |

| Blue (calorie-free and dark) | Cognition, dark blue also awakening/enlightenment | Akṣobhya | Centre (or n/a) | Air | Acrimony → "Mirror-similar" awareness | Pad |

| Ruddy | Dearest, compassion | Amitābha | West (or South) | Fire | Attachment → Discernment/ bigotry | Me |

| Blackness | Death, death of ignorance, awakening/enlightenment | – | n/a (or East) | Air | Hum |

The five colors (Sanskrit pañcavarṇa – white, green, yellow, blue, red) are supplemented past several other colors including black and orange and gold (which is commonly associated with xanthous). They are commonly used for prayer flags also every bit for visualizing deities and spiritual energy, construction of mandalas and the painting of religions icons.

Indo-Tibetan visual art [edit]

Indo-Tibetan Buddhism visual art contains numerous esoteric figures and symbols. There are different types of visual art in Indo-Tibetan Vajrayana. Mandalas are genre of Buddhist fine art that contains numerous symbols and images in a circumvolve and are an important element of tantric ritual. Thangkas are textile paintings which are commonly used throughout the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist world.

Tibetan Buddhist deities may frequently assume different roles and are thus fatigued, sculpted and visualized differently according to these roles. For example, Green Tara and White Tara which are dissimilar aspects of Tara that have different meanings. Greenish Tara is associated with protecting people from fear while the White Tara is associated with longevity. Shakyamuni Buddha may be seen in (pale) yellow or orangish skin and Amitabha Buddha is typically ruddy. These deities may also concord various attributes and implements in their hands, like flowers, jewels, bowls and sutras. Depictions of "wrathful deities" are frequently very fearsome, with monstrous visages, wearing skulls or bodily parts. They likewise may carry all sorts of weapons or fierce tools, like tridents, flaying knives and skull cups. The fierceness of these deities symbolizes the fierce free energy needed to overcome ignorance.[22]

Vajrayana Buddhism oft specifies the number of feet of a Buddha or bodhisattva. While ii is mutual there may also be ten, sixteen, or 20-4 feet. The position of the feet/legs may also have a specific meaning such every bit in Green Tara who is typically depicted as seated partly cross-legged but with one leg down symbolising "immersion within in the absolute, in meditation" and readiness to step forth and aid sentient beings past "appointment without in the globe through pity".[22]

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

In Tibetan Dzogchen thought, rigpa is symbolized by the white A inside of a circular rainbow.

-

-

State emblem of Mongolia with windhorse, iii jewels and dharma bike

-

White elephant with mani (jewels)

-

Manjushri with the flaming sword symbolizing prajna (wisdom).

-

Container for Buddhist Relics in Shape of Flaming Sacred Jewel

Symbolic concrete attributes [edit]

Ii Burmese Buddhist monks

Tibetan Buddhists with prayer beads (mala)

Buddhist material and visual culture every bit well as ritual tools (such as robes and bells) take oftentimes developed various symbolic meanings which are commonly shared by Buddhist sects effectually the globe.

Robes and baldness [edit]

The style and design of the robes of a monastic oft indicate the sect of Buddhism, tradition or country, they belong to. In most Buddhist cultures, the Buddhist monastic robe represents a renunciant monastic. Different traditions, sects of Buddhism (and different countries) volition accept robes of different colors as well as dissimilar styles or ways on how they wear it. Once Buddhism spread throughout China back in sixth century BCE,[25] information technology was seen incorrect to show that much skin, and that's when robes to cover both arms with long sleeves came in to play.[26] In Tibet, it accept changed over time and they show both their shoulders as well as having a 2 piece attire rather than one. Shortly thereafter, Nihon integrated a bib along with their long sleeve robe called a koromo. This was a clothing piece fabricated specifically for their schoolhouse of Zen which they practice in Takahatsu that involves the monks of Japan wearing a straw hat.[27]

Shaving ones head is another ritual and symbolic act virtually Buddhist monastics complete before entering a monastic lodge. To shave ones head merely signifies ones readiness to enter into the monastic path and abandon the worldly life.[28] [29]

Tools [edit]

Buddhist monks traditionally carry a begging bowl, and this is another mutual symbol of Buddhist monastics around the world (even though non all mod Buddhist traditions make use of the traditional practice of begging for i's food).

In all sects of Buddhism, bells are often used to signify the showtime of rituals or to marker time.[30] They apply the bell to detain away the bad spirits and have the Buddha protect them at the time of their ritual. Some sects telephone call this a part of the "Mystic Police" which is the get-go of a Buddhist ritual.[31] Other ritual tools include drums, wooden fish, trumpets, the keisaku, and the tantric the vajra and bell.

Physical gestures [edit]

Another form of symbolism of the Buddhist is the joining of your hands together at prayer or at the time of the ritual (añjali mudrā).[32] Buddhist compare their fingers with the petals of the lotus blossom. Bowing down is another form of symbolic position in the act of the ritual, when Buddhist bow in front of the Buddha or to another person they aren't bowing at the concrete (the homo or the statue) but they are bowing at the Buddha within of them (the homo) or it (the statue).[33]

Notable symbols [edit]

Buddhist flag [edit]

The five-colored flag have been designed in Sri Lanka in the 1880s with the help of Henry Steel Olcott. The six vertical bands of the flag represent the six colors of the aura which Buddhists believe emanated from the body of the Buddha when he attained Enlightenment.[34] [35] [36] [37]

Dharma wheel [edit]

A Dharma Wheel with a lotus half-roundel and lion base, from Amaravati.

The Dharma wheel (dharma-chakra) is ane of the primeval Buddhist symbols. It is an ancient Indian symbol of sovereignty and auspiciousness (also as the sun god Surya) which pre-dates Buddhism and was adopted past early Buddhists.[38] It appears in early on Buddhist sites such equally Sanchi and Bharhut, where information technology is a symbol of the Buddha himself. The Dharma wheel also represents the Dharma (Buddha's teaching, the ultimate truth).[39] [twoscore] [41] The main idea of this symbol is that the Buddha was seen as a person who "turned the wheel", which signifies a great and revolutionary moment in history (i.eastward. the pedagogy of the Buddha's Dharma at Varanasi). While the Buddha could have become a great king, he instead chose to become a great sage.[42] [43] [38] Illustrations from early on Buddhist sites likewise as Buddhist texts like the Mahavamsa, indicate that the worship of Dharma wheels on pillars ("wheel pillars", cakrastambha) was a common practice in early Buddhism.[44]

Bodhi tree from Sanchi complex topped with a chatra (majestic umbrella)

The Dharma wheel is thus also a regal symbol, indicating a male monarch who is a chakravartin ("Turner of the Wheel").[38] In the Buddhist scriptures, it is described as a imperial treasure of great, world class kings, a perfect cycle with a grand spokes.[45] Because of this, it was thus also used past the Mauryans, especially Ashoka (in the Pillars of Ashoka).[46] According to Karlsson "the association between the numbers of the spokes and a special Buddhist doctrine is a later interpretation and not present in early on Buddhist fine art." Early on Buddhist depictions contain wheels with various number of spokes (viii, xvi, 20, 25 and 32).[47]

Bodhi tree [edit]

The Bodhi Tree (Pali: bodhirukka) was a ficus (ficus religiosa) which stood is on the spot where the Buddha reached awakening ("bodhi"), chosen the bodhimanda (place of awakening). This tree has been venerated since early Buddhist times and a shrine was built for it. Offerings to the Buddha were offered to the tree.[48] The Bodhi tree (oftentimes paired with an empty seat or āsana) thus represents the Buddha himself, besides as liberation and nirvana.[49] Branches and saplings from the Bodhi tree were sent to other regions too. It is said that when the Buddha was born, the Bodhi tree sprung upward on the bodhimanda at the same time.[48] The worship of trees is an aboriginal Indian custom which tin can be found as far back as in the Indus Valley Civilization.[50]

The evolution of the Butkara Stupa; note the add-on of more than elaborate chatras (royal umbrella)

Stupa [edit]

Stūpas (literally "heap") are domed structures which may derive from ancient Indian funerary mounds.[51] The earliest Buddhist stupas are from near the 3rd century BCE.[52] In the early on Buddhist texts, the Buddha's actual relics (śarīra, the bones leftover from cremation) were said to have been placed in diverse stūpas and therefore, Buddhist stūpas are by and large symbolic of the Buddha himself, particularly his passing away (final nirvana).[53] [54] [55] It may even accept been a belief of some early Buddhists that the presence of the Buddha or the Buddha's power could be institute in a stūpa.[56]

Other relics belonging to the Buddha's disciples were as well enclosed in caskets and placed in stupas. Caskets with relics of Sariputta and Moggallana were found in Sanchi stupa number 3, while stupa number 2 contains a casket with relics from 10 monks (according to inscriptions).[57] Stūpa were venerated by Buddhists, with offerings of flowers and the like.[58]

Initially, Buddhist stūpas were simple domes which developed more elaborate and complex forms in later periods.[59] Over fourth dimension, the fashion and pattern of the stūpa evolved into unique and distinct regional styles (such equally Asian pagodas and Tibetan chortens).

Animals [edit]

Lion [edit]

Snowfall Lion, 1 of the types of Lions in Buddha symbolism.

Early Buddhist art contains various animals. These include lions, nāgas, horses, elephants, and deer. Most of these are often symbolic of the Buddha himself (and some are epithets of the Buddha), though they may also be depicted every bit merely decorative illustrations depending on context. According to Jampa Choskyi, while the animals are considered to be symbols for the Buddha, lions are the symbols of the bodhisattvas or also known equally the sons of the Buddha.[60] Though the king of beasts, is a symbol of royalty, sovereignty, and protection, is used equally a symbol for the Buddha, who is also known as the "lion of the Shakyas". Buddha's teachings are referred to as the "King of beasts'southward Roar" (sihanada) in the sutras, which symbolizes the supremacy of the Buddha's teaching over all other spiritual teachings. When looking at the shrines on the iconography, the lions symbolize another office, which they are considered the bodhisattvas who can exist seen as the sons of the Buddha. [60]

Elephant [edit]

Tibetan painting of a Buddhist elephant

The Buddha was likewise symbolized by a white elephant, another Indian symbol of majestic power. This symbol appears in the myth of Queen Maya when the Buddha takes the course of a white elephant to enter his mother's womb. Though the characteristics that are emphasized are the brute'southward forcefulness and steadfastness, these are the ones that become the symbol for the individual's mental and physical strength. The other way that the elephant is also a symbol of responsibility and earthiness.[threescore] When looking at the myth in Bharat almost elephants, the way that the myth goes is that the Airavata and the flying elephants would exist used as a vehicle for transportation. The elephant was said to be seen seemingly emerging from the white body of water, these animals were seen as having special powers with ane being the ability to produce rain.[sixty] Not only, were they considered to accept the ability to produce rain, in Indian society, just they were also are a symbol of good luck and prosperity, and since they were Kings would ain them and even used them in wars.[sixty] The white elephant can too be seen as a symbol of mental strength, the elephant would start as a gray elephant that is rampant when the listen is uncontrollable. As the individual continues to practice dharma and can tame their mind, the grey elephant now becomes a white one, which is a symbol for strong and powerful, who only destroys in the directions that are willed past the individual. The tusks are too seen every bit an keepsake of the Seven Majestic Emblems. However, Gangpati or Ganesh is known to exist an elephant-faced deity which is a form of the bodhisattva of Avalokitesvara. While, the elephant is seen as a deity when in the form of Avalokitesvara, the fauna has used transportation for Tathagata Aksobhya and the deity Balabadra. Similar the panthera leo, the elephant is seen every bit a guardian of temples and the Buddha. [lx]

Horse [edit]

Some of the characteristics that are emphasized most the horse are their loyalty, industriousness. and swiftness. [60]These characteristics tin exist seen in the riderless horse (representing the Buddha'due south royal horse, Kanthaka) symbolizes the Buddha'due south renunciation, and can exist seen in some depictions of the "Slap-up Renunciation" scene (forth with Chandaka, the Buddha'due south attendant property upward a regal umbrella). Meanwhile, deer represent Buddhist disciples, as the Buddha gave his first sermon at the deer park of Varanasi. In terms of Buddhism, the equus caballus is a symbol of energy and effort when practicing dharma, forth with the air or Prana that will run through the channels of the trunk. The "Wind Equus caballus" is the transportation of the listen and can exist ridden on. The deity that is associated with the equus caballus is Lokesvara also known equally Avalokitesvara, who also takes the grade of a horse. When looking at Buddhist iconography, the equus caballus is seen supporting the throne of Tathagatha Ratnasambhava. While they are used for support for Tathagatha Ratnasambhava, the beast is used as transportation for deities and dharma protectors, known as Mahali and the horse-faced deities, an example of this is Hayagriva.[60]

Naga [edit]

The Buddha is as well often called a "great nāga" in the sutras, which is a mythical serpent-like being with magical powers. However, this term is as well by and large indicative of the greatness and magical power of the Buddha, whose psychic power (siddhi) is greater than that of all gods (devas), nature spirits (yakkha), or nāgas. Another important nāga is Mucalinda, male monarch of the nāgas, who is known for having protected the Buddha from storms.

Peacock [edit]

A Buddhist monument with peacocks.

The peacock has multiple distinctly different symbols for which information technology is considered in different parts of the world and religions; all the same, in Buddhism, the peacock is a symbol of wisdom. The fashion they are continued to the bodhisattvas is by the peacock's power to eat a poisonous plant without getting afflicted by the establish, which correlates with the bodhisattva'south path toward enlightenment. The bodhisattva'southward path begins with delusions, ignorance, desire, lastly hatred, which all can be translated into moha, raga, dvesa. The opening of the colorful tail of the peacock can be compared to the enlightenment of the bodhisattva. The tradition that comes with the symbol of the peacock is when the bodhisattva becomes aware. The bodhisattva'due south trunk is adorned with five brightly colored feathers (red, bluish, dark-green, and others) that can be seen on the body. During the ceremony, the bodhisattva eats the same poisonous plants equally the peacock, every bit information technology happens, the feathers slowly change colors since, like the peacock, these individuals are non worried nigh the impairment that may come to them. Essentially the peacock is a symbol of the change from the path of want to the path of liberation. The deities that are associated with the peacock is Amitabha, who happens to represent desire and attachment into changes into liberation. [threescore] Along with the peacock existence a symbol in Buddhism, birds as a whole can be seen to be autonomously of the mantra said during "Cycle of Law", which has "Aum or Om Mani Padme Hung or hum rhi" every bit the individual symbols. When said together, the translation of the mantra is "Adoration to the jewel in the Lotus Amen". Co-ordinate to Tseten Namgyal. states that the symbols represented as "Om corresponding angels, Mani representing demons, Padme as men, hum equally quadrupeds srhi as birds and reptiles".[61]

Garuda [edit]

Garuda is too known every bit the rex of the birds. When looking at the origins of the name it comes from Gri significant to swallow since he devours snakes. The way he is represented in iconographies, he tin either exist seen with the upper body of a human being, that has large eyes, a beak, short blue horns, xanthous pilus standing on the finish, a bird's claws and wings. In Hinduism, he tin can be represented as a human with wings. However, when looking at the symbolism of Garuda, it represents the space element and the ability of the sun. Though when looking at the representation from a spiritual view, Garuda represents the spiritual energy that will devour the delusions from jealousy and hatred (represented past snakes). Since he represents the space element, this includes the openness that can be seen when he stretches his wings. Though, when looking at Buddhism specifically, he tin correspond the dana paramita, when the sun's rays requite life to the earth. The deity that Garuda is associated with is Amoghasiddhi, which is the vehicle of the deity. Through this, he is besides the vehicle form of Lokishvara Hariharihar vahana. However, he is a deity of his own, who is said to exist able to cure the bites of snakes, epilepsy, and diseases caused by nagas. Garuda tin be plant in toranas which are the semicircular tympanum that stands above the temple doors. Forth with an emerald that happens to exist named Garuda rock which is said to be protection confronting toxicant. Images of the deity are on jewelry as protection confronting the bites of snakes.[threescore]

Prevention of killing animals in Nihon [edit]

During the early days in Nippon, some places in the country would there were some places in the country that would allow the killing of animals in the region. However, Buddhism was transmitted to the country by China via the Korean peninsula. 1 of the teachings that resonated with the Japanese people was the basic laws of Buddhist ethics that had a part of the laws included the commandment to not impale which was similar to the principle of benignancy or jin, 仁. So from the 7th century onwards, the rulers would prohibit the killing of animals since the animals would be a symbol of benevolent rule for these rulers. What this meant for the animals that were kept by imperial officials included dogs, falcons, and cormorants to proper noun a few who were used for hunting purposes were to be set free. Their offices one time used for hunting were abolished afterwards on and the personnel who worked at that place would be transferred. Though the longevity of these decrees did not final long, the decrees had a long-lasting effect on the norms, values, and beliefs of at least the upper class of Japanese society for the next several hundred years. [62]

Lotus [edit]

Lotus and triratna at Sanchi

The Indian lotus (Nelumbo nucifera, Sanskrit: padma) is an ancient symbol of purity, detachment and fertility, and it is used in various Indian religions.[63] In Buddhism, the lotus is also another symbol for the Buddha and his enkindling. In the Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha compares himself to a lotus (in Pali, paduma). Merely like the lotus blossom comes upwards from the muddy h2o unstained, the Buddha is said to transcend the world without stains.[64] [65] [63] The Indian lotus also appears in early Buddhist sites like Sanchi and Bharhut. It is also the specific symbol of Amitabha, the Buddha of the Lotus family unit, as well as Avalokiteshvara (i.e. Padmapani, the "lotus holder"). In Tantric Buddhism, it is as well symbolic for the vagina every bit well as for chakras (often visualized as lotuses).

Triratna [edit]

Some other early on symbol is the triratna ("three jewels"), also called a trident (trishula) in non-Buddhist contexts. According to Karlsson, the ancient pre-Buddhist symbol was initially seen equally a "weapon against enemies or Evil."[66] In Buddhism, this symbol after came to represent the Buddha, Dharma (teaching, eternal law), and sangha (Buddhist monastic community).[66]

Vajrasana [edit]

The Buddha throne, or empty seat/platform (āsana, afterward associated with the "vajra seat", vajrāsana) is a symbol of the Buddha. The vajra seat or enkindling seat represents the place where he sat downwards (in Bodh Gaya) to meditate and attained enkindling. Information technology thus also represents the place of awakening (bodhimanda) and is thus similar to the Bodhi tree in this regard.[67] [68] [69] In early Buddhist art, the vajra seat may also be depicted as an empty seat (often under a tree) or a platform. All the same, these seats or platforms may not specifically symbolize the "vajra seat" itself and may just be an altar or a symbol of the Buddha.[70] A vajra seat or empty seat may also be decorated with lotuses or be depicted as a giant lotus (in this example, it can exist referred to as a "lotus throne").

The Emerald Buddha; annotation the elaborate umbrella (chatra) decorated with Bodhi leaves and the lotus throne

Footprints [edit]

Buddha footprint at the entrance of the Seema Malaka temple, Sri Lanka.

The Buddha footprint (buddhapāda) represents the Buddha. These footprints were often placed on stone slabs, and are usually decorated with some other Buddhist symbol, such as a Dharma bike, swastika, or triratna, indicating Buddhist identity.[71] [72] According to Karlsson, "in the 3rd century AD equally many every bit twelve signs tin exist seen on slabs from Nagarjunakonda. At that time we can constitute such signs as fishes, stupas, pillars, flowers, urns of enough (purnaghata) and mollusc shells engraved on the buddhapada slab".[73]

Chhatra [edit]

The Buddha as a flaming pillar, Amaravati, Satavahana period

In some early reliefs, the Buddha is represented by a imperial umbrella (chatra). Sometimes the chatra is depicted over an empty seat or a horse, and it is sometimes held past an bellboy figure like Chandaka. In other depictions, the chatra is shown over an illustration of the Buddha himself.[74] It too represents royalty and protection, besides as honor and respect.

Indrakhila [edit]

The Indrakhila ("Indras post") which appears in early Buddhist sites has sometimes been interpreted as a symbol for the Buddha (but it could just be a symbol of auspiciousness). This is usually "a series of formalized lotus plants one in a higher place the other, with artificial brackets in the borders from which hang jewelled garlands and necklaces of lucky talismans betokening both worldly and spiritual riches. At the acme in that location is a trident and at the bottom a pair of footprints".[75]

Flaming pillar [edit]

Some other symbol which may indicate the Buddha is a "flaming pillar".[76] This may be a reference to the Twin Phenomenon at Savatthi and the Buddha's magical abilities.

Swastika [edit]

Endless knot in a Burmese Pali Manuscript

The svastika was traditionally used in India to represent good fortune. This symbol was adopted to symbolize the auspiciousness of the Buddha.[77] The left-facing svastika is often imprinted on the chest, feet or palms of Buddha images.[78] The swastika was as well a symbol of protection from evil.[79] The ancient swastika (which are also Chinese characters, mainly 卍 and 卐) is common in Buddhist art. It is widely used in East asia to represent Buddhism, and Buddhist temples. Buddhist symbols similar the swastika have also been used as a family emblem (mon) by Japanese clans.[80]

Endless knot [edit]

The countless knot is a symbol of good luck. Information technology may also represent dependent origination.

Pair of fishes [edit]

A pair of fishes (Sanskrit: matsyayugma) represent happiness and spontaneity too equally fertility and affluence. In Tantric Buddhism, information technology represents the left and right subtle body channels (nadis). In China, information technology often represents fidelity and bridal unity.

Dhvaja [edit]

The victory banner was a military symbol of victory, and symbolizes the Buddha's victory over Mara and the defilements (an epithet for the Buddha is the "conqueror"; in Sanskrit, Jina).

Vase [edit]

Bumpa ritual vase used in Tibetan empowerments. The peacock plumage and the gemstone symbolize Dzogchen practices of Trekcho and Thogal.

A treasure vase, which represents inexhaustible treasure and wealth, is also an attribute of wealth deities similar Jambhala, Vaishravana and Vasudhara.

Conch trounce [edit]

A conch shell represents victory, the spreading the teachings of the Buddha far and broad, and the aspect of oral communication. It is blown on auspicious events to denote (and also invite) the deities or other living beings of the happening of the auspicious effect, such as marriages (in Sri Lanka).

Ever-burning lamp [edit]

The "ever-burning lamp" (changmingdeng) is "an oil lamp kept in the monastery that in theory was never allowed to burn out". This was used as a symbol for the Buddhist teachings and for the "heed of correct enlightenment" (zhengjuexin).

Ruyi [edit]

Ruyi may accept been used equally a baton held by a speaker in a chat (a talking stick), and subsequently became imbued with different Buddhist meanings.

Wooden fish [edit]

A Japanese "wooden fish" (mokugyo), a wooden percussion instrument used in chanting

Wooden fish symbolized vigilance.

Tibetan ritual conch shell trumpet with dragon

Votive lamps from a Taiwanese temple

Ring staff [edit]

The ring staff is traditionally said to exist useful in alerting nearby animals as well as alerting Buddhist donors of the monk's presence (and thus is a symbol of the Buddhist monk).

Number 108 [edit]

The number 108 is very sacred in Buddhism. Information technology represents 108 kleshas of humankind to overcome in order to achieve enlightenment. In Japan, at the finish of the twelvemonth, a bong is chimed 108 times in Buddhist temples to stop the onetime yr and welcome the new one. Each ring represents i of 108 earthly temptations (Bonnō) a person must overcome to achieve nirvana.

Vajra [edit]

A vajra is a ritual weapon symbolizing the backdrop of a diamond (indestructibility) and a thunderbolt (irresistible strength). The vajra is a male polysemic symbol that represents many things for the tantrika. The vajra is representative of upaya (skilful means) whereas its companion tool, the bong which is a female symbol, denotes prajna (wisdom). Some deities are shown holding each the vajra and bell in split hands, symbolizing the wedlock of the forces of compassion and wisdom, respectively.

In the tantric traditions of Buddhism, the vajra is a symbol for the nature of reality, or sunyata, indicating endless creativity, authorization, and skillful activity.

An musical instrument symbolizing vajra is as well extensively used in the rituals of the tantra. It consists of a spherical central section, with two symmetrical sets of five prongs, which arc out from lotus blooms on either side of the sphere and come to a bespeak at two points equidistant from the centre, thus giving it the advent of a "diamond sceptre", which is how the term is sometimes translated.

Various figures in Tantric iconography are represented holding or wielding the vajra.

The vajra is made up of several parts. In the center is a sphere which represents Sunyata, the primordial nature of the universe, the underlying unity of all things. Emerging from the sphere are two viii petaled lotus flowers. Ane represents the astounding world (or in Buddhist terms Samsara), the other represents the noumenal world (Nirvana). This is i of the cardinal dichotomies which are perceived by the unenlightened.

Arranged equally effectually the mouth of the lotus are two, four, or eight creatures which are called makara. These are mythological half-fish, one-half-crocodile creatures made upwards of two or more animals, oft representing the union of opposites (or a harmonisation of qualities that transcend our usual experience). From the mouths of the makara come tongues which come together in a point.

The five-pronged vajra (with four makara, plus a central prong) is the most ordinarily seen vajra. There is an elaborate organisation of correspondences betwixt the five elements of the noumenal side of the vajra, and the phenomenal side. I important correspondence is between the 5 "poisons" with the five wisdoms. The five poisons are the mental states that obscure the original purity of a being's mind, while the five wisdoms are the five well-nigh important aspects of the aware mind. Each of the five wisdoms is also associated with a Buddha effigy (see besides Five Wisdom Buddhas).

Bell [edit]

The vajra is virtually always paired with a ritual bong. Tibetan term for a ritual bell used in Buddhist religious practices is tribu. Priests and devotees band bells during the rituals. Together these ritual implements represent the inseparability of wisdom and pity in the enlightened mindstream. During meditation ringing the bong represents the sound of Buddha teaching the dharma and symbolizes the attainment of wisdom and the understanding of emptiness. During the chanting of the mantras the Bong and Vajra are used together in a variety of different ritualistic means to represent the matrimony of the male and female principles.

The hollow of the bell represents the void from which all phenomena arise, including the sound of the bell, and the clapper represents form. Together they symbolize wisdom (emptiness) and compassion (form or appearance). The sound, like all phenomena, arises, radiates forth and then dissolves back into emptiness.

Enso [edit]

Ensō Calligraphy by Kanjuro Shibata Xx

In Zen, ensō (円相, "circular form") is a circumvolve that is manus-drawn in ane or ii uninhibited brushstrokes to express a moment when the mind is free to allow the body create.The ensō symbolizes accented enlightenment, strength, elegance, the universe, and mu (the void). It is characterised by a minimalism built-in of Japanese aesthetics.The circle may be open or airtight. In the onetime case, the circle is incomplete, allowing for movement and development too every bit the perfection of all things. Zen practitioners relate the idea to wabi-sabi, the beauty of imperfection. When the circle is closed, it represents perfection, akin to Plato'southward perfect course, the reason why the circle was used for centuries in the structure of cosmological models Once the ensō is drawn, one does not change it. It evidences the character of its creator and the context of its creation in a cursory, continuous period of time. Ensō exemplifies the various dimensions of the Japanese wabi-sabi perspective and artful: fukinsei (disproportion, irregularity), kanso (simplicity), koko (basic; weathered), shizen (without pretense; natural), yugen (subtly profound grace), datsuzoku (freedom), and seijaku (tranquility).

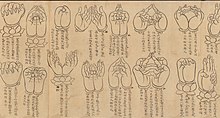

Japanese scroll depicting various mudras

Mudras [edit]

Mudras are a series of symbolic paw gestures in Buddhist art. At that place are numerous mudras with different meanings. Mudras are used correspond specific moments in the life of Gautama Buddha.

Other symbols [edit]

Mandala of Vajradhatu (the vajra realm)

- Some deities such equally Prajñaparamita and Manjushri are depicted as holding a flaming sword, symbolizing the ability of wisdom (prajña).

- The gankyil or "wheel of joy" symbol, which can symbolize dissimilar sets of three ideas.

- Various kinds of jewels (mani, ratna), such as the cintamani or "wish fulfilling jewel".[81]

- Buddhist prayer chaplet (mala), which originated in India as a way to count prayers or mantras and commonly take 108 beads.[82]

- The wish fulfilling tree (kalpavriksha)

- The fly-whisk, which is a tool to drive away insects and thus symbolizes non-harming (ahimsa).[83]

- Mandala, Yantra.

Groups [edit]

A Chinese Metallic Cup stand up with the eight auspicious symbols (14th century)

The eight auspicious signs [edit]

Mahayana Buddhist art makes utilize of a common set of Indian "eight auspicious symbols" (Sanskrit aṣṭamaṅgala, Chinese: 八吉祥; pinyin: Bā jíxiáng , Tib. bkra-shis rtags-brgyad). These symbols were pre-Buddhist Indian symbols which were associated with kingship and may originally have included other symbols, like the swastika, the srivasta, a throne, a pulsate and a flywisk (this is all the same role of the Newari Buddhist eight symbol listing).[84]

The most common set of "Eight Auspicious Symbols" (used in Tibetan and Due east Asian Buddhism) are:[85] [86]

- Lotus flower (Skt. padma; Pali. Paduma)

- Endless knot (srivasta, granthi) or "curl of happiness" (nandyavarta)

- Pair of golden fish (Skt. matsyayugma)

- Victory imprint (Skt. dhvaja; Pali. dhaja)

- Dharma wheel (Skt. Dharmacakra Pali. Dhammacakka)

- Treasure vase (kumbha)

- Jeweled Parasol (Skt. chatra; Pali. Chatta)

- White Conch Shell (sankha)

Symbols on Anxiety of Buddha [edit]

Buddha footprints frequently bear distinguishing marks, such as a Dharmachakra at the center of the sole, or the group of 32, 108 or 132 cheering signs of the Buddha, engraved or painted on the sole.

See as well [edit]

- Buddhist art

- Chinese art

- Indian art

- Japanese fine art

- Korean art

- Religious symbolism

- Tibetan art

References [edit]

- ^ a b Coomaraswamy (1998), pp. 1–five.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 168.

- ^ Karlsson, Klemens. Face to confront with the absent Buddha: The formation of Buddhist Aniconic art. Diss. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2000.[1]

- ^ Freiberger, Oliver. "The Meeting of Traditions: Inter-Buddhist and Inter-Religious Relations in the West". Archived from the original on 2004-06-26. Retrieved 2004-07-15 .

- ^ Chauley (1998), p. iv.

- ^ a b Karlsson (2000), p. xi.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 174.

- ^ a b Chauley, G. C. (1998) pp. ane–16.

- ^ "The Fine art of Buddhism". The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Smithsonian Institution. 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ^ Prapod Assavavirulhakarn (1990). The Ascendency of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, p. 133. University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ Kieschnick (2020), p. 85.

- ^ Kieschnick (2020), pp. 100, 113–115, 138–139, 153.

- ^ Williams, Charles Alfred Speed (2006). Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs: A Comprehensive Handbook on Symbolism in Chinese Art through the Ages, p. 170. Tuttle Publishing.

- ^ Williams, Charles Alfred Speed (2006). Chinese Symbolism and Fine art Motifs: A Comprehensive Handbook on Symbolism in Chinese Fine art through the Ages, pp. 83–87. Tuttle Publishing.

- ^ Prasetyo, Lery (2019-08-01). "THE SPIRITUAL AND CULTURAL SYMBOLS IN A MAHAYANA BUDDHIST TEMPLE 'VIHARA LOTUS' SURAKARTA". Analisa: Journal of Social Science and Religion. 4 (1): 59–78. doi:ten.18784/analisa.v4i01.788. ISSN 2621-7120.

- ^ Kieschnick (2020), p. 83.

- ^ see for example: Ensō: Audrey Yoshiko Seo (2007). Zen Circles of Enlightenment. Shambhala Publications.

- ^ Beer (2003), p. 87.

- ^ Beer (2003), p. 92.

- ^ Beer (2003), p. 95.

- ^ Beer (2003), pp. 98–112.

- ^ a b c d e Sangharakshita. An Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism.

- ^ "Tibet Travel". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ "Shakya Statues". Retrieved 27 Aug 2015.

- ^ "Buddhism in Prc". Asia Social club . Retrieved 2018-10-28 .

- ^ "Get an Overview of the Robes Worn by Buddhist Monks and Nuns". ThoughtCo . Retrieved 2018-10-28 .

- ^ "Buddhist Monks' Robes: An Illustrated Guide". ThoughtCo . Retrieved 2018-x-eleven .

- ^ "Why practice Buddhists Shave their Heads?". world wide web.chomonhouse.org . Retrieved 2018-10-12 .

- ^ "Why practise Buddhist monks and nuns shave their heads? – Mahamevnawa Buddhist Monastery". Mahamevnawa Buddhist Monastery. 2018-04-20. Archived from the original on 2018-x-28. Retrieved 2018-x-28 .

- ^ "Buddhist Bells and Statues – Presentation | Art in the Modern World 2014". blogs.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2018-x-28 .

- ^ "The Pregnant of Burning Incense and Ringing Bells in Buddhism | Synonym". Retrieved 2018-ten-eleven .

- ^ "Why Buddhists Bring together Their Easily in Prayer | Myosenji Buddhist Temple". nstmyosenji.org . Retrieved 2018-10-12 .

- ^ 본엄 (2015-06-07), Why Do Buddhists Bow to Buddhas?, archived from the original on 2021-12-12, retrieved 2018-10-12

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2004-09-23. Retrieved 2004-07-fifteen .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Wayman, Alex. "The Mirror as a Pan-Buddhist Metaphor-Simile." History of Religions xiii, no. four (1974): 251–269.

- ^ "The Buddhist Flag". Buddhanet. Retrieved ii April 2015.

- ^ "The Origin and Meaning of the Buddhist Flag". The Buddhist Council of Queensland. Retrieved two Apr 2015.

- ^ a b c Karlsson (2000), pp. 160, 164.

- ^ Chauley, Chiliad. C. (1998) pp. one–20.

- ^ T. B. Karunaratne (1969), The Buddhist Bike Symbol, The Wheel Publication No. 137/138, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy • Sri Lanka.

- ^ John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Fine art, p. 524.

- ^ Pal, Pratapaditya (1986), Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.–A.D. 700, p. 42. Academy of California Press

- ^ Ludowyk, E.F.C. (2013) The Footprint of the Buddha, Routledge, p. 22.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 161.

- ^ T. B. Karunaratne (1969), The Buddhist Bike Symbol, The Wheel Publication No. 137/138, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy • Sri Lanka.

- ^ Chauley, G. C. (1998) pp. 1–20.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 162.

- ^ a b G.P. Malalasekera (2003) Dictionary of Pali Proper Names, Volume 1, pp. 319–321. Asian Educational Services.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), pp. 98–102.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 158.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 175.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 175.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), Pagoda.

- ^ Buddhist Architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, p.140-174

- ^ Karlsson (2000), pp. 164–165, 174–175.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), pp. 183–184.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 181.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 182.

- ^ Lee Huu Phuoc (2009). Buddhist Architecture, p.149-150, Grafikol

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Choskyi, Jampa (1988). "Symbolism of Animals in Buddhism". Gakken Co. Archived from the original on 2017-04-xv. Retrieved xv Oct 2021.

- ^ Namgya, Tseten (2016). "Significance of 'Eight Traditional Tibetan Buddhist Auspicious Symbols /Emblems' (bkra shis rtags brgyad) in 24-hour interval to solar day Rite and Rituals". EBSCOhost . Retrieved 15 October 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Vollmer, Klaus (2006). "Buddhism and Violence" (PDF). The Lumbini International Research Found. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-20. Retrieved fifteen October 2021.

- ^ a b Karlsson (2000), pp. 165–166.

- ^ AN 10.81, '"Bāhuna suttaṃ".

- ^ AN 4.36, "Doṇa suttaṃ".

- ^ a b Karlsson (2000), p. 168.

- ^ Ching, Francis D. 1000.; Jarzombek, Marker M.; Vikramaditya Prakash (2017). A Global History of Architecture, p. 570. John Wiley & Sons.

- ^ Huu Phuoc Le. Buddhist Architecture, p.240

- ^ Buswell Jr., Robert E.; Lopez Jr., Donald South. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, "Bodhimanda". Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400848058.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 166.

- ^ "Footprints of the Buddha". Buddha Dharma Instruction Clan Inc. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-11 .

- ^ Stratton, Carol (2003). Buddhist Sculpture of Northern Thailand, p. 301. Serindia Publications. ISBN 1-932476-09-1.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 158.

- ^ Marshall, John. "A Guide to Sanchi", p. 31.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), pp. 100–102.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), pp. 48, 120.

- ^ Swastika: SYMBOL, Encyclopædia Britannica (2017)

- ^ Adrian Snodgrass (1992). The Symbolism of the Stupa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-81-208-0781-5.

- ^ Karlsson (2000), p. 169.

- ^ (Japanese) Hitoshi Takazawa, Encyclopedia of Kamon, Tōkyōdō Shuppan, 2008. ISBN 978-4-490-10738-8.

- ^ Williams, Charles Alfred Speed (2006). Chinese Symbolism and Fine art Motifs: A Comprehensive Handbook on Symbolism in Chinese Art through the Ages, p. 413. Tuttle Publishing.

- ^ Kieschnick (2020), pp. 116–124.

- ^ Williams, Charles Alfred Speed (2006). Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs: A Comprehensive Handbook on Symbolism in Chinese Art through the Ages, p. 201. Tuttle Publishing.

- ^ Beer (2003), p. ane.

- ^ Beer (2003), pp. ane–fourteen.

- ^ Zhou Lili. "A Summary of Porcelains' Religious and Auspicious Designs." The Bulletin of the Shanghai Museum 7 (1996), p.133

Bibliography [edit]

- Anderson, Carol (2013-10-11). Hurting and Its Ending. doi:x.4324/9781315027401. ISBN9781136813252.

- Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. ISBN978-1-932476-03-iii.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda Chiliad. (1998). Elements of Buddhist Iconography. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

- Chauley, G. C. (1998). Early Buddhist Fine art in India: 300 B.C. to 300 A.D. Sundeep Prakashan

- Kapstein, Matthew T. (June 2004). "Tadeusz Skorupski: The Buddhist Forum, Book VI. 9, 269 pp. Tring: The Plant of Buddhist Studies, 2001". Message of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 67 (2): 266. doi:10.1017/s0041977x04420163. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162316190.

- Karlsson, Klemens (2000). Face to Confront With the Absent Buddha - The Formation of Buddhist Aniconic Art. Uppsala Academy.Lokesh, C., & International Academy of Indian Culture. (1999). Dictionary of Buddhist iconography. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture.

- Seckel, Dietrich; Leisinger, Andreas (2004). Before and beyond the Image: Aniconic Symbolism in Buddhist Fine art, Artibus Asiae, Supplementum 45, iii–107

- Xing, Guang (2004-11-10). The Concept of the Buddha. doi:ten.4324/9780203413104. ISBN9781134317004.

- Kieschnick, John (2020). The Affect of Buddhism on Chinese Material Culture. Princeton University Press.

External links [edit]

- Sacred Visions: Early on Paintings from Central Tibet, an exhibition itemize from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Buddhist symbolism

- web site showing iconic representations of the 8 auspicious symbols along with explanations

- the eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism — a study in spiritual evolution

- Full general Buddhist Symbols

- Tibetan Buddhist Symbols

- Buddhist Tantric Symbols

- Buddhist Symbols: the Eight Auspicious Signs

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhist_symbolism

0 Response to "Meaning of Red Circle and Gold Circle Japanese Buddhist Art"

Post a Comment